Why Do You Buy? Unlearning Consumption, Day 1

A new series that's all about hitting the reset button on our buy-now-think-later culture.

Why should you care about the words coming out of my keyboard? I've worked in online marketing for 13 years which gives me a unique vantage point from the other side of the curtain.

To kick off the Unlearning Consumerism Series, I'm zeroing in on the big 'why'—because it's not just about cutting back; it's about understanding the root of our shopping habits and rethinking our approach to consumption.

If you’re keen on rethinking your buy-button reflex, consider hitting subscribe instead—it’s the one-click guaranteed not to clutter your life (and it’s free).

Know someone else wrestling with their inner shopper? Sharing this article might just be the nudge they needed, and it helps support my work, win/win.

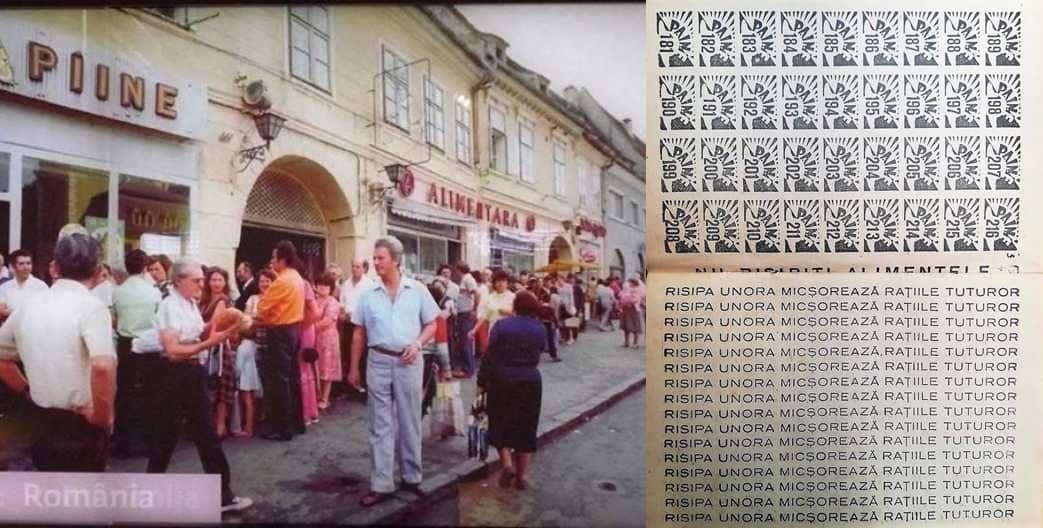

My parents waited 5 years to get a car.

They waited 5 years to buy a car, not because they couldn't afford one.

But because they weren't allowed to buy one. There was a list. You had to wait for your turn.

You had to wait for your turn to buy bread, milk, oil, and sugar.

You had to wait for your turn to buy fabric, jackets, and underwear.

You had to wait to buy. There wasn't enough. There was never enough.

Availability not affordability

When communism ended, fearing a currency collapse, my parents bought gold jewelry; it was the only thing they could buy.

In the new capitalist system that followed, they opened and operated a business that would end up supporting our family for 30 years. They are now happily approaching retirement.

Even though I grew up in a capitalist society, I was raised not to over-buy. This was because:

of my parents' post-communist PTSD and fear of lacking,

wasteful consumption was seen as taking away from everyone's pot,

of a strong "we can do it ourselves" mentality that characterizes Eastern Europe to this day.

We never bought mayonnaise, my mother made it herself. And running the risk of sounding ridiculous, I was probably 18 when I realized mayonnaise is something one can buy in a store, like ketchup, which she also made. She made pickles and jams and a whole catalog of canned goods that filled our basement. Do what you can, buy what you can not.

Appealing to the gender norms of that time, my dad fixed what he could. When they were finally able to buy a car, he tinkered with it to the point of being able to disassemble it and put it back together. Fix what you can, buy what you can not.

My mother still works and still makes mayonnaise.

My dad still thinks he can fix everything with a motor.

My parents are the norm, not the exception.

Every conversation about consumerism sparks an argument about capitalism which always seems to bring about a reference to communism - especially from people that have never lived through communism.

But this isn't a conversation about communism, or capitalism, or any other 'ism.

It's an answer to a question.

Why do you buy?

You buy because you can.

If you live in the global north, you probably don't remember a time in which you couldn't buy.

It feels counter-intuitive, doesn't it?

Like your brain can't wrap itself around it?

Money is supposed to solve needs, to take you on vacation, to make the world go round. It's meant to be taken from underneath your proverbial mattress and placed under someone else's.

Yesterday's reality sits in stark contrast to today's buying habits.

In societies rich with abundance, the line between want and need has blurred to the point of being indistinguishable.

Have you ever paused to consider whether your purchases were made out of want or need?

If basic necessities like food, shelter, and clothing were prioritized, the wants were considered luxuries, something to be indulged in only when the means allowed.

But thanks to the industrial revolution, and our increased disposable income, markets now overflow with options.

From the latest tech gadgets to the newest fashion trends, you're inundated with hedonic products masquerading as necessities that promise to enhance your lifestyle and status.

Personal happiness in a can, now yours for the low price of $9.99 per month.

This abundance fosters an illusion of infinite choices, where every desire not only can be met but should be.

Why do you buy?

You buy because you have choices.

You buy because you don't know where your "needs" end and "wants" begin.

It's (mostly) not your fault.

As marketing's reach has become more pervasive and powerful, it's not just products that are being sold to us; it's our very identities.

We've gradually come to see ourselves, and are seen by others, as consumers.

Tell me what you buy and I'll tell you who you are.

This transformation doesn't just influence what we buy; it deeply impacts how we view ourselves and make decisions.

With each purchase acting as a statement of who we are, the pressure mounts—not just to choose, but to choose wisely, as if our self-esteem and social standing are perpetually on the line.

This shift has made the act of buying more than just about acquiring goods; it's about affirming our place in the world, often leading us down a path where our decisions are as much about crafting an image as they are about fulfilling a need.

We willfully see ourselves as cogs in a consumption machine.

The fundamental problem with this attitude towards consumption is that it sets up a rigged game in which it's impossible to feel as though you're doing well enough.

This distinction between want and need is, in part, obscured by data-rich marketing that knows how to appeal to your human biases and weaknesses.

Just think of the notifications you see on your devices - the vibrations, buzzing, red dots, and flashing lights - they're purposefully built to mimic naturally occurring signs of danger.

Think of the infinite scroll and algorithm-driven recommendations purposefully used to keep you plugged in a daze for as long as possible.

Think of all of the ads that are constantly bombarding you with the latest must-haves, somehow suggesting that your life is incomplete without them.

The technological seduction, the FOMO, the discount culture, the illusion of scarcity, the collector's joy...

You never really stood a chance.

Why do you buy?

You buy drawn by the magnetic pull of marketing

You buy to communicate your identity and social standing.

It feels like everywhere you turn, something or someone is nudging you, whispering that you're always lacking.

Yet, this fleeting satisfaction from acquiring something new is just that—fleeting. The itch it scratches fades away quickly, replaced by the next desire, lurking just around the corner. And always, the reassurance: 'Don't worry, you can afford it.

Whether it's the growth of an apple, the molding of a plastic IKEA bowl, or the making of a car. The potential ecological damage, significant as it may be, takes a backseat to financial cost.

This product is yours if you can afford it.

Not if the planet can afford it.

Not if our ecosystem can offset the damage.

If you have enough green pieces of paper to “manifest” this product into the world.

This is probably why 99% of the physical products bought by Americans are trashed within 6 months.

There is no real sense of ownership over the products we buy or a sense of responsibility over how it's disposed of.

Imagine if you lived long enough, and had the chance to observe the wide-reaching effects of your actions extending behind you.

Suppose you stopped just enough to witness the extensive chain of outcomes unfurling from your simplest actions, whether good or bad. Could you grow an appreciation for lasting impact, for what persists?

We've done a fantastic job at pulling the curtain over the extraction, production, distribution, and consumption process. We don't see the forests burning, or the child labor; what we see is the neatly packaged Amazon box with the sleek branding and promised benefits.

What we see is the garbage truck taking our trash to some magical land.

Why do you buy?

You buy because you don't see where the waste goes.

You buy because the human lifespan is too short to see the consequences of our actions.

Fortunately (or not) the effects of this ecological harm go beyond the smog hovering over New Delhi and into everyone's air.

From the bleaching of coral reefs in Australia to the inability to grow the exact grapes needed for champagne in France. Global warming does not discriminate, and we're ever so gently waking up to it.

And yet... what is life without our comforts?

We choose to eat genetically modified and overpriced strawberries, 365 days a year instead of waiting for their natural harvesting season.

We choose to use the car for a 5-minute drive instead of using public transportation or just using our limbs as they were intended.

We choose to crank up the AC at the smallest feeling of discomfort.

We choose to buy plastic bottles, bags, and containers instead of reusable ones.

We choose to buy new, instead of second hand.

We make a lot of easy and convenient choices on the promise of saving time and effort.

Unfortunately, the more comfort you need, the more is taken from the Earth to provide you with it.

Why do you buy?

You buy because of convenience.

Suppose your great-great-great-grandchild were to come visit you from the future. They're actively living through all of the harms scientists are currently warning us about. "Stop!" they'd say "That plastic Eiffel Tower trinket you bought from France will be here 200 years from now!"

"Relax!" you'd say. "Haven't you heard? We're building technology to address these problems."

"You innovate," your great-great-great-grandchild would note, "but each solution brings new challenges. Your electric cars reduce emissions but increase the demand for lithium, cobalt, and nickel mining which can harm ecosystems and communities."

I don't have an offspring of my own but I like to play these types of scenarios in my head for fun to increase my anxiety.

Unfortunately, in all of my thought experiments, I haven't yet found a happy medium between comfort and environmental stability. I haven't found an answer better than:

Sell responsibly, buy thoughtfully.

That's what it all comes down to.

Yes, corporations suck. Fossil fuel sucks. Kim Kardashian taking her private jet for a 30-minute flight sucks.

Yes, they account for the majority of the pollution. But they pollute, in part, to create the products we buy.

There’s enough blame to go around, we live in an imperfect system.

None of us can single-handedly overthrow a society dedicated to limitless consumption. But you can stop buying into the delusion that there are no consequences AND, most importantly, that there are no solutions. You can face the facts and make a change.

Our economic model relies on assumptions of endless growth and resource availability. But the Earth is finite. What happens when we reach its limits?

What if instead of betting everything on the promise of future technology, we could also focus on changing consumption habits, promoting circular economies, and valuing experiences and relationships over material possessions?

Why do you buy?

You buy because you still think the future will get better.

In Romania, my generation is dubbed the "Revolution Babies" - Copiii Revoluției - because we were born in the year communism fell—1989, to spare you a Google search.

Growing up, I was constantly reminded of my fortune to live in a post-communist era, enjoying the fruits of capitalism, assured that the future held even greater promise. And I embraced that belief.

And yes, I acknowledge my luck and privilege, a status shared by anyone reading this. However, my optimism for the future has waned, and it boils down to a simple, everyday reality: I don't make my own mayonnaise, I buy it.

Why do you buy?

You buy because the price is the only gatekeeper because the abundance of choices makes it hard to distinguish needs from wants, because marketing brilliantly taps into your sense of identity, because convenience promises to simplify life, and because, despite everything, you hold onto the belief that the future will be better.

What do you think?

What’s the last thing you bought?

Was it a want, or a need?

Was this worth reading?

Use the heart to let me know ❤️

Thank you for writing this. I look forward to reading the rest of this series. And everything else you write.

This article was fantastic. Your family background is something many (most?) either haven't experienced or haven't thought of in a while.